Tag: The Sister Queens

The Sister Queens Featured in “A Visual Preview of the Spring Season”

I am very pleased that The Sister Queens is one of fifteen books featured by Sarah Johnson in a “visual preview” of historical fiction releases piquing her interest this spring. Sarah recently received the 2012 Louis Shores Award in recognition of her excellence in book reviewing (both at her fantastic blog, Reading the Past, and in other forums). Thanks to Sarah’s post my own mental “to be read” pile has just expanded by a couple of absolutely fascinating novels I’d not yet heard of and likely wouldn’t have discovered for months yet sans Sarah.

Women’s Work — Trobairitz, the First Female Composers of Western Secular Music

In the High Middle Ages the Occitan speaking world – of which Provence was a part – brought Europe a group of poet composers called troubadours. These musicians and their tradition of composing songs of courtly love, chivalric bravery, and bawdy humor quickly spread throughout much of Europe. The influence of troubadours and their work-product can hardly be overstated. Their verses were a stepping stone for virtually all of western literature that followed. Without the troubadours it is unlikely we would have Dante or Chaucer just to scratch the surface.

Who were the troubadours? Probably not who most people think.

Popular imagination tends envision troubadours as itinerant. In fact, they often attached themselves for long periods of time to a single court, enjoying the patronage of a nobleman or woman.

Nor were they vagabonds (romantic as that might seem). The earliest troubadours were members of the nobility, including the highest ranks. Ruling Dukes and Counts could be troubadours (e.g. William IX of Aquitaine a very early troubadour, and grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine, was a Duke). Even Kings—including Richard I of England; Thibaud I, King of Navarre (and Count of Champagne for good measure); and Alfonso X, King of Castile—were known to dabble as poet-musicians. Only gradually did individuals of the lower classes (merchants and tradesmen generally, rather than the truly poor) join their numbers. This makes sense given the fact that troubadours wrote a type of sophisticated verse that would be greatly facilitated (and may arguably have required) the writer to be a “person of letters” (educated).

Contemporary audiences also tend to think of troubadours as exclusively male. They were not. In medieval Occitania composing original poetry and setting it to music could be and was women’s work as well as men’s. The women who pursued this occupation were called trobairitz and they were the FIRST female secular poets and female composures of secular music in the western world.

Of the more than four hundred troubadours whose names are still known to scholars today, about twenty–or roughly 5%–can be positively identified as women, but women may well have been a higher percentage (is not always easy to distinguish the work of a trobairitz from that of a troubadour and it is also possible that some women used male pseudonyms for their work).

Like my Sister Queens, the female trobairitz came almost exclusively from the Occitan cultures (there are know trobairitz from Provence, Auvergne, Languedoc, Dauphine, Toulouse and Limousin). This is likely not a coincidence.

Circumstances in early 13th century Occitania created the perfect storm for the emergence of these secular women poets. Women of this region administered great estates—dispensing justice and defending property—at a time when such roles were far less common elsewhere in Europe. Why? First, they were able to inherit and govern territory in their own right. But perhaps more importantly, a nearly continuous string of crusades resulted in a large loss of Occitan men either temporarily or permanently (when a nobleman died or simply decided to stay in the Crusader States). And while their fathers, husbands and brothers were absent women throughout Occitania were left in charge of administering family holdings.

What the trobairitz wrote is as startling as the sudden emergence of these woman poets. Trobairitz used their voices to emphasize their desires and to assert their right to have love and passion in their lives. Consider this excerpt from a work of the most well known trobairitz, the Countess of Dia:

I should like to hold my knight

Naked in my arms at eve,

That he might be in ecstasy

As I cushioned his head against my breast . . .

I grant him my heart, my love,

My mind, my eyes, my life.

These are the words of noble women with enough self-assurance to express and defend not only their actions in taking lovers but their emotions and their passions. They also often emphasized feminine values both setting forth ideal love and in defining the valorous male. Pretty remarkable for the 13th century.

The period of the trobairitz was fleeting. They first appear in the literature early in the century and most of their writings are dated up to and through the 1260s. By 1280 they had disappeared entirely. While this may seem sad, it can be taken as a more positive reminder that history is not linear—even those periods when the roles of women were heavily circumscribed have been punctuated by moments of female progress and power.

If you are interested in hearing the words of the trobairitz as they were meant to be—sung—there are a number of excellent recordings (e.g. In Time of Daffodils: Songs of the Trobairitz, The Sweet Look And The Loving Manner – Trobairitz, Love Lyrics and Chansons de Femme from Medieval France or The Romance Of The Rose – Feminine Voices From Medieval France)

I will leave you with one of my favorites–a rendition of a poem by the Countess of Dia

The Best Gift an Author Could Ask for — Marvelous Endorsements for The Sister Queens

Last holiday season Santa outdid himself—I got my debut book deal for Christmas.

The past year has been full of wonderful experiences, from working with my very astute and caring editor at NAL to receiving my first reader’s review on goodreads. Each one of these pre-publication events shines like a foil-wrapped Christmas package in my memory.

Some of year’s most precious gifts came from fellow historical fiction writers—luminaries of the genre actually. I’ve been honored to receive a number of marvelous endorsements (known as “cover blurbs” in the business) for The Sister Queens from authors whose work I both read and admire. I am pleased and proud to unveil them – and the fabulous front cover that NAL created for The Sister Queens – at my newly renovated “My Books” page.

Here, with profound thanks to their authors, are a few blurbs to whet your appetite:

In her debut novel, The Sister Queens, Sophie Perinot breathes life into two of history’s most fascinating siblings. What Philippa Gregory did for Anne and Mary Boleyn, Perinot has done for Marguerite and Eleanor of Provence. This is without a doubt one of the best novels I’ve read all year!”

—Michelle Moran, author of Madame Tussaud

Every page of The Sister Queens for me was like a morsel to savor. The Sister Queens is one of the most beautifully written books I have read in a very long time. Absolutely superb! I will certainly be adding it to my ‘keeper’ shelf.”

—Diane Haeger, author of The Queen’s Rival

Sophie Perinot’s debut tour de force, The Sister Queens, gives the reader a detailed and racy look into the very public and most intimate lives of English and French royalty. The sister queens have two very different personalities, yet Perinot’s skills allow a modern woman to see herself in them and root for them both. This sweeping, compelling novel is a medieval, double-decker lifestyles of the rich, famous, and fascinating.”

—Karen Harper, author of The Queen’s Governess

For more endorsements, including kind words from authors Elizabeth Loupas, Christy English, Leslie Carroll and Anne O’Brien please visit the “My Books” tab.

P.S. Santa, no need to leave anything under the tree for me this year, I am one of the luckiest ladies around.

Still a Few Hours Left to Enter to Win THE SISTER QUEENS

For all the “last minute” types out there, it’s down to the wire for the goodreads giveaway of The Sister Queens. So what are you waiting for?

This is your chance to get your hands on an ARC of the novel pre-release. And remember if you are reader of my blog and a winner, I’ll be delighted to send along a signed bookplate for your copy. Just contact me through my author website. Best of luck!

How Belva Lockwood Got Me Thinking About Overlooked Women in History

Once upon a time I was young. No, honestly. Then as now I was a history nerd—big time. In fact (trivia alert), I was the first member of my graduating class to declare a major in history. Anyway, one day the younger me was given a postcard by her Woman’s History professor. A postcard showing the black and white image of Belva Lockwood. This image as a matter of fact.

It took me a while to discover the importance of this gift, delivered, as I remember it, with no real explanation beyond the mild-mannered comment, “I thought you might like this.” With age and distance I now realize my professor gave me the postcard to galvanize me to action; to make me angry—not at him but at the way history was taught and who got left out. You see Belva Lockwood was the first woman to have her name on the ballot for President of the United States (yes, I know Victoria Woodhull “ran” but her name did not appear on official ballots and votes for her were never tallied). She was also the first woman to be admitted to practice before the Supreme Court (though mind you she had to write to President Grant just to get the law diploma she’d earned and it took an act of Congress to see her admitted before the High Court). But I’d never heard of her.

That DID make me angry, and it also made me think. Just what does a woman have to do to be noticed, historically speaking? Give birth to a King? Have her head chopped off? How can that be when there were so many women throughout history who did so much more? Even today, Belva remains only the tip of the “over-looked” iceberg. And because we continue to under-represent women in history and underestimate their activities readers—both of non-fiction history and historical fiction—often think writers get it WRONG when they accurately report what historical female characters did.

I recently saw an example of this in a book review. A reviewer took Author X to task because her female main-character pressed her right to rule her own territories. “How dare the author suggest,” and I am paraphrasing here, “that a woman in the Middle Ages would assert such authority, or would even have the desire to rule in her own right!” The reviewer went on to castigate Author X for imposing modern feminist ideas on long dead women. But the truth is plenty of women held territory (and titles) in their own right during the time period of the author’s book. The reviewer was just wrong—likely because he/she had never heard of such women. I remember wondering what said reviewer would make of the fact that my main characters’ uncle, Thomas of Savoy, was Count of Flanders only by marriage and lost that title when his wife died and her title passed to her SISTER. My guess is the particular reviewer would think that bit of history was made-up, feminist-revisionism as well.

It is time to recognize, as consumers of history and historical fiction, that women have filled many, varied, roles throughout the centuries—even if we haven’t always heard about them. Some women did extra-ordinary things with those roles (e.g. just like male rulers, some female rulers were better at it than others), but the fact women held such roles wasn’t, in and of itself, necessarily as extraordinary as modern audiences seem to think. In each period of history we need to look at the specific facts rather than relying on broad assumptions. For example, to assume things were necessarily better for women later in history than they were earlier is to incorrectly posit a linear progression in women’s rights and opportunities.

I am happy to say that, imo, there’s a lot of really wonderful historical fiction celebrating women who have been historically overlooked these days. There are also fabulous books that examine “big name” historical women in new ways—as more than “ornaments of royal courts” or “mothers of kings.” Personally, I am very interested in telling the stories of women who are more obscure than they deserve to be. Probably because of that darned postcard. When I stumbled upon a footnote in a history of Notre Dame de Paris about Marguerite of Provence (her image is carved over Notre Dame’s Portal Rouge) and her sisters I had a Belva Lockwood moment. Clearly these young women (all of whom made significant political marriages) were celebrities of the High Middle Ages. Marguerite and Eleanor were the queens of France andEngland for heaven’s sake! Yet I had never heard of them. I made up my mind right then to tell their story.

I wish Professor T was alive today. I’d send him a copy of my book and I’d put the Belva Lockwood postcard in it—as an excellent bookmark and a thank you of sorts.

For The First Time Ever You Can WIN a Copy of The Sister Queens

I am pleased to announce that my wonderful publisher (have I mentioned lately how much I love them?) is making twenty-five (yes! 25) copies of The Sister Queens available for a giveaway over at Goodreads! The contest started today (November 3rd) and runs to December 3rd.

So if you are one of the folks who (so kindly) have told me that you just cannot wait for my debut to hit shelves in March, now is your chance to score a copy before the novel’s release date. Make that a free copy – which is even better right?

If any of the lucky winners are readers of this blog I will throw in a little something extra. Use the contact form at my author website to send me the good news (plus your address) and I will mail you a signed bookplate to put inside your copy.

Best of luck!

A Game of “10 Questions” with Kayla at the Pittsburgh Historical Fiction Examiner

I am happy to be back at the Pittsburgh Historical Fiction Examiner today as part of Kayla’s “10 Question” series. So, if you’ve ever had a pressing desire to know which five people from history I’d like to host at a dinner party, or what I drink when writing (no – not cocktails), now is your chance to find out.

Or, if you are interested in learning more about the inspiration for my debut novel, The Sister Queens, and the amazing women at my story’s heart (Marguerite and Eleanor of Provence), I did this earlier interview at The Examiner on those topics.

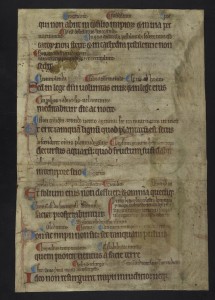

A Treasure Trove of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts Goes Digital

Lovers of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts rejoice (I am certainly celebrating)! The University of Pennsylvania, with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, has finished digitizing a significant number of its rare Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts so that researchers and history-junkies alike can peruse them from the comfort of their own homes.

While the Rare Book and Manuscript Library on the sixth floor of Van Pelt Library includes over 2,000 pre-19th century western manuscripts, the on-line collection – called ““Penn in Hand: Selected Manuscripts” – currently offers access to facsimiles of just over 1,400 documents. I’ve checked out the site – in fact I’ve just finished enjoying a 1566 letter from Charles IX of France to his ambassador at the Spanish court of Phillip II – and there are many convenient ways to browse and search the manuscripts, including by year, by language and by author.

So what are you waiting for? You KNOW you want to look.

On This Day in Her Story #8: A Reunion of The Sister Queens

In October of 1254 Henry III and Eleanor of Provence receive permission from Louis IX of France to travel through his kingdom while making their way back to England from Gascony.

King Henry is eager to visit the grave of his mother, Isabella of Angoulême, at Fontevrault Abbey. Eleanor is excited by the prospect of seeing her sister Marguerite (Queen of France) after nearly two decades of separation. The stage is set for a family reunion between Provencal sisters and a meeting of their royal husbands during the Christmas season.

They’ve Got Authors Covered – Design Departments Not Writers Create Book Covers

Have you ever walked into a bookstore, picked up a historical novel set in renaissance Italy and thought “my goodness WHAT is this headless woman on the cover wearing? Her gown is SO obviously Tudor!” Yeah, me too. And here’s the thing, before I started writing historical fiction I might have drawn some erroneous conclusions based on such a book cover.

First, I might have concluded that “author X” hadn’t done her research or just didn’t care that her cover model was wearing a gown from the wrong period. Since becoming an author I’ve learned that this is probably not the case. Shall I tell you a secret? Authors have VERY limited influence on the covers of their books.

I am NOT saying that good publishers don’t seek author input before holding a cover conference. My editor asked me for examples of existing covers that I loved as well as examples of covers I didn’t like. She encouraged me to explain why I felt as I did. She also asked me to collect images from fine art imbued with the feeling I wanted my cover to have, and to submit descriptions and pictures of what my 13th century sisters might have worn.

What I AM saying is my cover was still a big surprise when I saw it. So if you LOVE the cover of The Sister Queens, I am glad but, please, give credit where it is due. I did not create the cover painting (you should be thankful for this – profoundly thankful), the cover artist did. And folks in the design department picked that gorgeous lettering. So send your warm and fuzzy thoughts (or compliments) their way. And if you HATE the cover of my book (or any author’s book) please spare me a note upbraiding me.

This leads me to the second flawed conclusion I might have drawn back in my “fan-but-not-a-writer” days: covers exist to accurately portray a period of history, or a scene from a book. Nope. Sorry. Some covers may do those things, but covers in general are designed for one reason and one reason alone – to sell books. This is precisely why authors don’t (and probably shouldn’t) design them.

I never viewed covers as sales tools until I signed my book contract. But believe me once you have a book coming out selling books is foremost in your mind. I want to sell books, and more than that, I want to sell books to people who are not ME. Therefore, what I would personally like to see on the cover of my book runs a distant second to what a majority of book-buying, cash-carrying potential readers will find attractive. And the truth is I am not in a position to predict what will catch the eye of the average book buyer. I am not trained to do that, nor have I conducted studies or otherwise made it my business to keep my fingers on the pulse of such things. The folks in my publisher’s art and design departments, on the other hand, ARE in a position to predict what will make a reader reach out and lift The Sister Queens off a table full of books all looking for a home. They have been designing covers for years. That’s why design departments and not authors get the final say over what book covers looks like.

Perhaps the folks designing the cover for a historical novel know that a certain color gown makes books jump off the shelf and into readers’ hands, so they use that color even if it may not be precisely “period.” They might even (gasp) put Tudor gowns on non-Tudor-era women because books about Tudors sell like hotcakes and they are hoping to entice readers of Tudor historical fiction to pick up, and ultimately try, something new. Who can say? As an author I certainly can’t. And as a reader I am now careful to examine covers with a different eye than I did in my pre-writing days—I may still judge the book by its cover, but I no longer judge that book’s author.

Authors are in the business of writing books, design and art departments are in the business of covering them.