Tag: historical fact

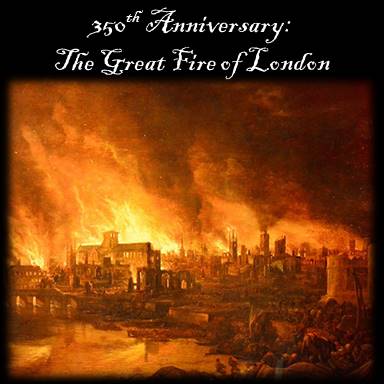

A Solemn Anniversary

Today marks 350th Anniversary of the ignition of the Great Fire of London, which burned for days (September 2–5, 1666). Driven by gale force winds and accompanied by a panic stoked by rumors of foreign involvement, the blaze destroyed more than 13,000 dwellings leaving upwards of 70,000 Londoners homeless. It also destroyed businesses and significant landmarks in including St. Paul’s Cathedral. Remarkably, the official death toll for the three day conflagration was only 6. However, it should be remembered that many of the lower and lower-middle-class victims may not have been recorded.

Historical Tidbits Part II

My countdown of the weird, wild and wonderful of the late Valois era continues. Part II of my video series of historical tidbits is now complete. Enjoy! And, as always, if you want more (much more) Valois Court intrigue, pick up a copy of Medicis Daughter.

Because History is So Much Stranger Than Historical Fiction

I am constantly reminded that quite often the strangest things that are included in my books–the ones that cause readers to send me notes saying “really Sophie? really?” are NOT details that I created, but rather those that are historically verifiable. In the case of the French Valois court there were many historical tidbits that caused me to do a double-take, some of which made the finished novel, Médicis Daughter, and some of which didn’t.

Knowing that many of my faithful readers are as likely to geek out over these dramatic goodies as I was, I am creating a two part countdown of ten of the juiciest, weirdest, historical tidbits from my research into 16th century Valois France. Below is Part I. Enjoy!

Maundy Thursday in History and in my Books . . .

Today is Maundy Thursday. The final Thursday before Easter, Maundy Thursday commemorates the Last Supper—the event which established the Holy Eucharist. Historically Maundy Thursday is associated with powerful figures washing the feet of the marginalized (a King might wash the feet of a pauper—see the stained-glass depiction below—and this year Pope Francis will wash the feet of a dozen refugees) as Jesus washed the feet of his disciples. Evidence of the rite of Pedilavium (the Church’s term for this ceremonial foot washing) goes back to very ancient times and is considered a joyous rather than a solemn ceremony. The word “Maundy” comes from Latin for “command” and refers to Christ’s commandment to his disciples to “love one another as I have loved you.”

I cannot say when or why exactly I became slightly fixated on this particular religious observance, but Maundy Thursday makes multiple appearances in my work. It was included in the original draft of The Sister Queens (Louis, seen at the right, was a hugely penitent man who not only frequently washed the feet of the less fortunate but liked to eat the leftovers of meals consumed by his favorite leper). King Charles IX and Queen Catherine de Médicis observe the Lenten foot-washing tradition in Chapter 2 of Médicis Daughter. An occasion that finds a teenage Margot in no very good mood:

“Why do you pout?” My brother sidles up to me where I stand, watching Charles and Mother receive basins and ewers from the Cardinal de Bourbon. Nearby, a collection of Troyes’s paupers—mostly women and children—sit on a long bench, prepared to be the objects of royal Lenten piety.

“I did not realize I would be left out of some of the grandest ceremonies of the journey.”

Yesterday the King made a magnificent Entry into Troyes—riding beneath a canopy supported by dignitaries past elaborate set pieces and stopping to hear recitations of poetry written for the occasion. The residents of the city, from the wealthiest to the urchins roaming its streets, were permitted to witness it all. I was not. It seems the women of the court, even the Valois women, are not included in the proceedings that constitute a Royal Entry.

As for What’s Next . . . I can tell you this, Chapter 4 of my latest novel begins with a mumbled, “Last Supper” and Maundy Thursday marks some very dramatic events.

Black Rats, the Black Death, and the Changeability of History

What we “know” for certain in history often changes. New studies, new information, new scholarship can challenge and change accepted facts, and undercut theories that have stood for decades or even longer.

Witness this article in today’s Guardian newspaper reporting that a new work by a well known archaeologist declares the Plague of 1348-49 spread so quickly through London that the carriers were not black rats, as previously thought, but human beings themselves. Fascinating and a reminder that we ought not be too sanguine about what we know to be “the truth.”